Design is mid pt. 3

Getting fired and hired from a medial place

Part 3 of an ongoing mid career dilemma design practice, education and industry. Read part 2 here. Read part 1 here.

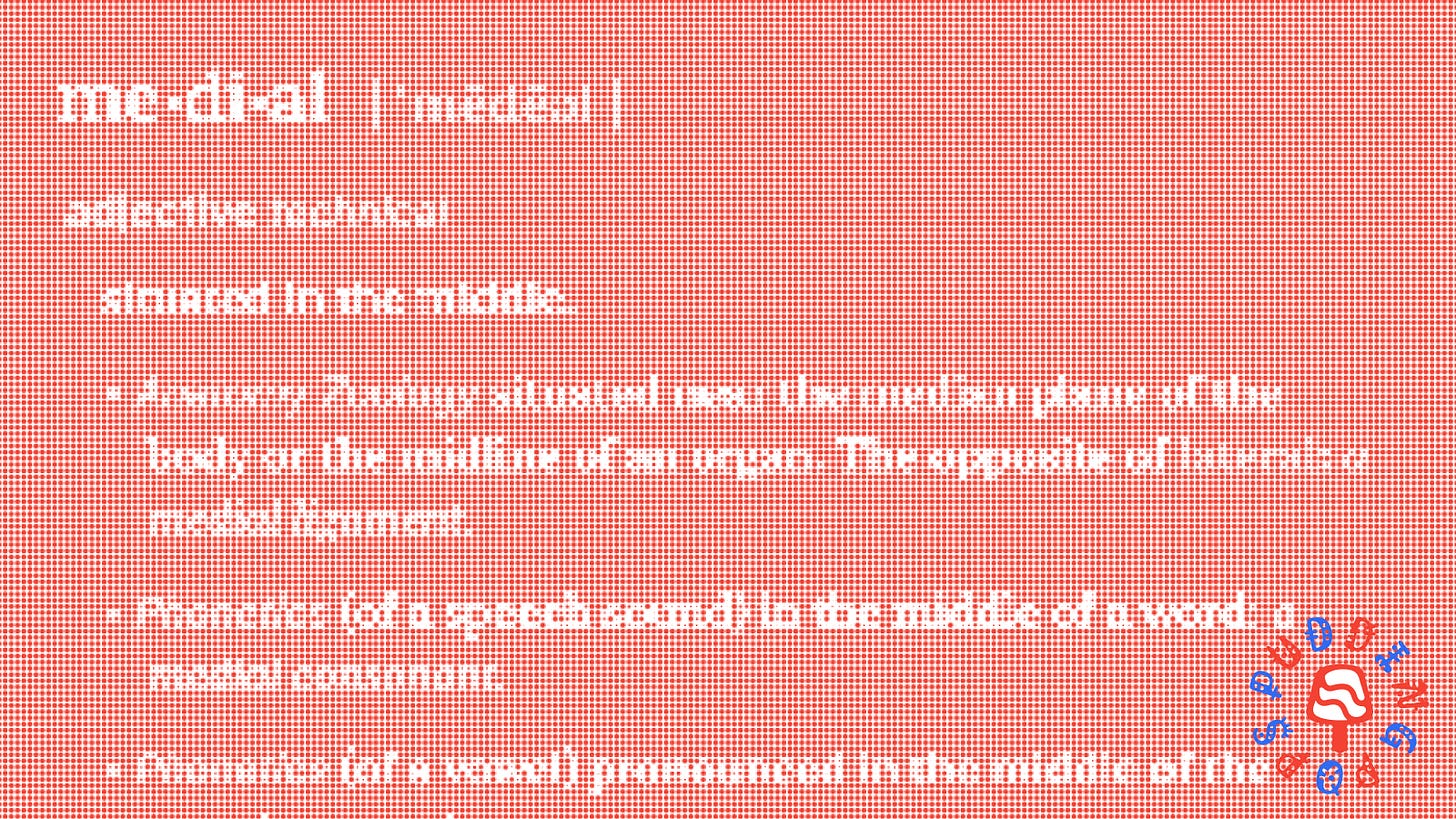

In this third installment of ‘design is mid’ I’ll begin with two issues. First, this particular essay is meandering and sprawling because of the various dots I’m trying to connect. Second, I think a clarification of the word ‘medial’ in my statement explains the provenance of my current dilemma and this series.

The dictionary definition of ‘medial’ is an adjective meaning ‘situated in the middle’. A derivative word of ‘medial’ is ‘medially’ and is used to clarify a thing’s location. Although sometimes I use ‘medial’ in a ‘mediary’ way, the word itself defines position. As a designer and person, I feel my practice of design is ‘situated in the middle’ of many things, places, subjects, mediums, students, colleagues and clients. I am situated between a brief and the work I do for the client. I am situated between my pedagogy and the making of my students. I am situated between Korea and America. It is true that the process of my work starts at a ‘medial’ position and becomes ‘mediary’, but the starting point is in the middle. I use my discipline of design to translate and interpret, author and edit, express and define, clarify and confuse to become a filter of the various inputs and outputs that exchange through my work. My process is highly informed by my lived experience as a Korean American and my privilege of being pushed and pulled across continents, histories and heritage. Now, I find myself in a medial career, which led me to contemplate how a young designer, or someone starting out in design, could get here today.

Looking back at my career, I was very lucky to have the training and education I received, but it also led to many haphazard experiences. Recently, I was listening to a podcast with the writer Hua Hsu and artist Andrew Kuo (two people I have long admired for their witty cultural criticism rooted in their Asian American experience). Hsu asks Kuo about his time at RISD and he begins his explanation by saying, “RISD is annoying.” I was, and probably still am, an annoying product of that school and was hired and fired for that exact reason from several jobs. To the annoyance of my last “boss”, I quit a good position at Vox Media right after being told that I would get a director-level promotion in three months. This is all to say that I’m not the best person to think about job descriptions and company hierarchies, but now I feel a responsibility to my students to advocate for more clarity in the workforce for design talent.

Having been “out of the game” for almost ten years, I turned to my friend L.A. Corrall to get a better idea of how designers work and succeed these days. L.A.’s career has spanned a variety of areas of design, working at agencies like Method, Wolff Olins and Collins. Most recently, he was Head of Design at Anomaly Los Angeles. When we caught up, he spoke about the various styles of management and promotion at his different jobs, but expressed general dismay about how unchanged many of the pathways for designers were. I too was disheartened to hear his anecdotes of peers skyrocketing to higher positions merely for their ability to fall into the right graces of Creative Directors and partners.

At Collins, L.A. did put a lot of effort into changing this culture by advocating for more formal reviews with designers. Now, I’m not a huge fan of this type of bureaucratic reporting, but in my experience, a level of self and peer review through was valuable for me. At Collins, L.A.’s efforts to create better feedback channels for designer performance also led him to build intermediate positions that acknowledged the different specialty areas of design. For example, he worked with a few designers whose roles were focused on motion design. He saw that the team did not get the right recognition at points in a project that required more specific advocacy. This led him to building a Motion Creative Director position and created space in a project’s development for motion work to be properly represented and shepherded. I found this type of specificity to be incredibly useful to graphic designers, because of the broad reaching nature of our work. This brings me to another dilemma I am tossing around in my head: the generalist vs. the specialist.

Recently, I was on a call with a friend who works on the sales side of marketing at a large tech company. Although he does engage with designers, his perspective represents the client in most designers’ experiences. He communicated a bit of frustration from his dealings with designers and a gap in skills. From his experience working at a large tech company working with a variety of designers, he encountered two types, generalists and specialists. Although he respected both styles of designer, he said for his area of work, the generalist was much more preferred. When I asked the qualities of the generalist, he immediately relayed ‘strong communication skills’ and outlined that, from his experience, a designer’s ability to explain and advocate for design was of outsized value in comparison to their formal craft. At a tech company like where he works at, the specialists exist, but are a few, select crew focused on a certain area of the company. At scale the desired expectations for a designer are, ironically, more abstract and general. This led me to think, what is keeping a design student from being hired into marketing teams for non-designer positions?

In 2018, Hongik University College of Design and Arts, where I am still faculty, was mandated to integrate four departments: Design and Media (foundations), Digital Media, Product Design and Communication Design. The impetus for this is hard to explain due to complicated policies from the Korean Board of Education and my own ignorance, but the new curriculum we created looked toward creating multifaceted designers. What followed was a four-year structure that included two-years of “foundation”, so that students could learn levels of coding and design strategy in addition to the more traditional 2-D, 3-D, drawing and art history courses. From the 3rd year on, students then start to specialize in their desired areas like UI/UX, graphic design, product design and digital art to name a few. The elective selection was left to the students, but node courses linked areas of design together. Hongik has now graduated four classes from the School of Design Convergence and I have been increasingly surprised by the changes. Contrary to our plan, students have created more specialized works. However, the generalist perspective is embedded in their process and in their ability to envision and execute a diverse range of outputs. To me, the new curriculum strengthened the core of our students’ approach to design, while leaving room in their final two years of study to explore an iterative range of outcomes. We will see how successful and needed our students are in terms of industry adoption, because it is hard to tell with the continued slowing of youth employment in Korea.

Admittedly, my musings about employment and promotion for designers comes from two personal sources. First, I have a lot of guilt about opting out of career advising for my Korean students. This may have been reasonable for the first three or four years of teaching in Korea, but I have to continued to refuse any sort of career advice for my students unless they wish to study aboard. Second, I too found myself applying to jobs in a vain attempt to “re-enter” industry after a decade in academia and independent practice. From these two points, I witnessed how dramatically different the landscape of design has become and encountered a huge opaque wall when applying to jobs. In many ways, there are more design jobs out there than when I graduated in 2006, but it is even harder to know what one does as a designer. Cutting through the jargon is a task in itself and it makes me wonder how a recent graduate can puzzle together a trajectory for their design skills. Not everyone is hiring for an interface designer, but the job descriptions ask for UI/UX experience. Not everyone is in need of a motion designer, but the job descriptions say motion experience is a plus. Not everyone is hiring for a brand designer, but the job descriptions say to elevate the brand. Unless the company has a design team who is publicly advocating for their work, it’s incredibly hard to know how design is utilized within a given company. In some ways, Hongik’s generalist vision is being affirmed by these opaque jobs and their multifaceted requirements. But I’d like to repeat an option that moves in the other direction: design jobs are no longer specialist positions, so stop hiring specialists.

Another line in my designer statement is that I am an advocate of Gunnar Swanson’s idea of teaching graphic design as a liberal art. Throughout the weeks I’ve been preparing this essay, I’ve had numerous conversations with people in various areas of design. I’ve sheepishly workshoped my idea of trying to convince employers in hiring design graduates as project managers or junior marketing staff. The responses have been varied, but I think everyone agreed that design students could benefit more from learning how to think and communicate, than deepen their technical skills. This is not to say abandon craft or profession, if anything, it affirms the importance of the core tools of design. I’ve seen this with my students at Hongik. The current tools and technology are easily learned and they show tremendous aptitude. However, when it comes to message, story, content, meaning and depth they thirst for more support and nourishment.

So, I say let the AI eat themselves and continue the important work that we love as designers from the middle position of past and future. Let’s keep building ladders of change to keep us connected to our craft and ideas. But let’s not be disheartened by the loss of jobs, because most of those jobs sucked anyways!