Design is mid pt. 2

The mid career questions keep flowing

Part 2 of an ongoing mid career dilemma design practice, education and industry. Read part 1 here.

Recently, I’ve been working with the designer and educator Shannon Doronio Chavez at VCFA, a low-residency MFA program where I teach. I highly encourage anyone interested in design education to follow her Instagram and keep an eye out for her posts on equity and diversity in the classroom. A few months ago AI came up in discussion and she articulated an incredible argument in response of one of my challenges regarding valuing the labor of design work. To better convey her thoughts, I asked her to reiterate her stance in words:

This may be my postmodernist bias showing, but I’m deeply skeptical of anything that claims to be “one-size-fits-all.” These solutions often rely on mathematical “averages,” producing watered-down approaches that overlook the richness and complexity of life. As society runs face first into the AI era—a realm shaped by biases embedded in algorithmic averages—cultural literacy and the ability to craft nuanced human centered stories will be an essential competitive skill for all storytelling professions.

Listening to Blake Lemoyne talk on AI I have this thought: We are facing a new threat of cultural colonization via AI, a technology that is trained on material fraught with western colonial bias. If we fail to learn how to critique its outputs, what will those using AI to study and create passively learn—or perpetuate?

I admit, this response sits well with me because I align with Shannon’s values, but it’s also an answer that encourages the kind of criticality that could maximize the productive potential of designers, especially in the coming near future where a narrowing of the discipline by emergent technologies threatens the practice. My shared viewpoint with Shannon is that the work we create as visual communicators, will ultimately be for humans.

Taking that assumption forward with an eye on the market, I think of the loss that happens when brands globalize and have poorly thought out localization plans. Without diverging too far into corporate branding, the point I’d like to link is that there is economic potential in speaking to different people (consumers) with inclusive specificity. This lost potential, the failure to make marginalized groups feel seen and heard, ultimately becomes a failure to the capture the productive participation of said groups. The downfall, or the tragic boredom of Modernism, particularly the presumptions of the International Style, was an example of designers failing to speak to people and instead speaking for them. The datasets and methods of data capture by AI companies like OpenAI are operating from equally presumptive and biased perspectives. Ultimately, this blindess is why, as an educator, I am stubbornly sticking to the value of creative voice and critical expression.

There is the catch 22. To maintain economic value for design work while the designer’s creative labor becomes more cerebral and abstract, a need or desire for quantifiable delivery persists. There are plenty of other professions and industries where the labor is immaterial, and yet the discipline is highly rewarded monetarily and professional disciplinarity is preserved, think of lawyers. Part of the failing of the creative capitalist structure is the inherent need to associate quantitative value to every action, so when the actions are less visible, then how do we bill by the hour? How do you pay for “brainstorming” and “concepting” and “storytelling”, while the productive creative labor is being made more efficient with AI technology?

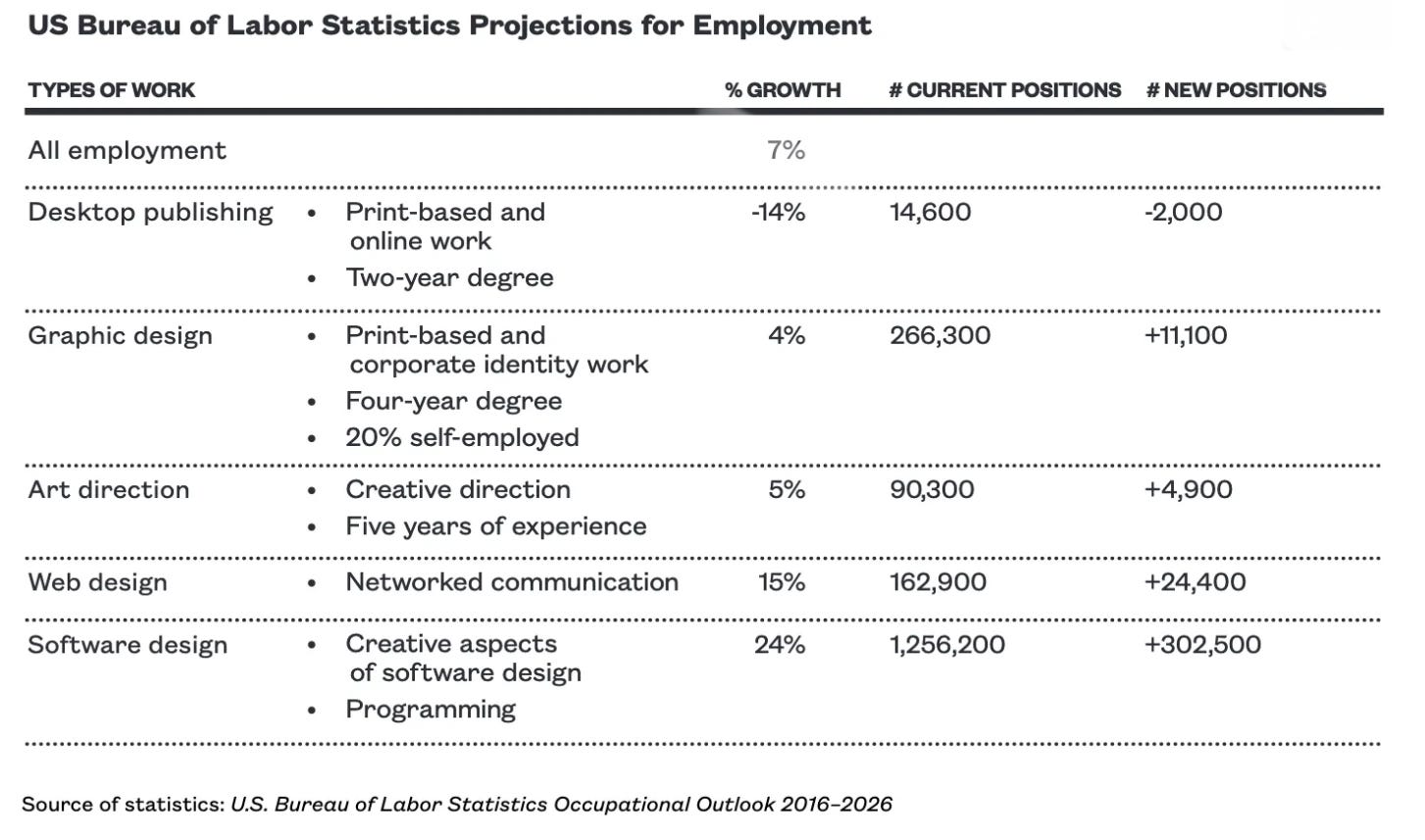

That said, there is a growing crisis about the economic value of pedagogical methods of diversity and creative voice and the same forces that are squeezing out these methods for efficiency are the very actors who have shifted the operations of designers today to be hyper-focused on productivity. The tech industry has tapered the design industry. I admit, there is potential damage to my own stubborn beliefs in how and what to teach young designers. All indications of industry movement points toward growth in positions that apply graphic design to the tech industry. But the breakneck speed of Silicon Valley add fuel to the worry that AI drastically cheapens the value of creative labor.

In regards to prosperity, I have rarely met a designer who aims to just hit a mid-salary range and pursue a career of secure mediocrity. To be clear, I am not dismissing this ambition and acknowledge that such an attitude exists. What I am trying to point out is that the design world often over-celebrates the million-dollar contracts, the six-figure salaries, the awards, and the glitz and glamor of “the creative” rather than focusing on professional issues that actually affect the majority of designers; matters like job security, health insurance, retirement savings, client relations, intellectual property, etc…

I have long been inspired by Gunnar Swanson’s essay “Graphic Design Education as a Liberal Art”, and even though my application of the idea has been more self serving, I ask is it wrong for design education to serve a more general purpose divorced from strict professional outcomes? Can a staff education be as useful or useless as an accounting degree?

I realize it haven’t or forth much of a solution to the mid-quandary of design and AI, but maybe this AIGA Design Futures Report can shed some light.